After Alabama Ruling, Time for a Serious Look at Ethics of IVF Industry

My latest article in Newsweek on a controversial court ruling.

I realize that IVF is a deeply personal issue for many people, and can appreciate that readers of Human Flourishing will have different views on the issues I discuss here. Regardless, I hope this article, originally published last week in Newsweek, helps us examine aspects of this industry that are often shielded from scrutiny.

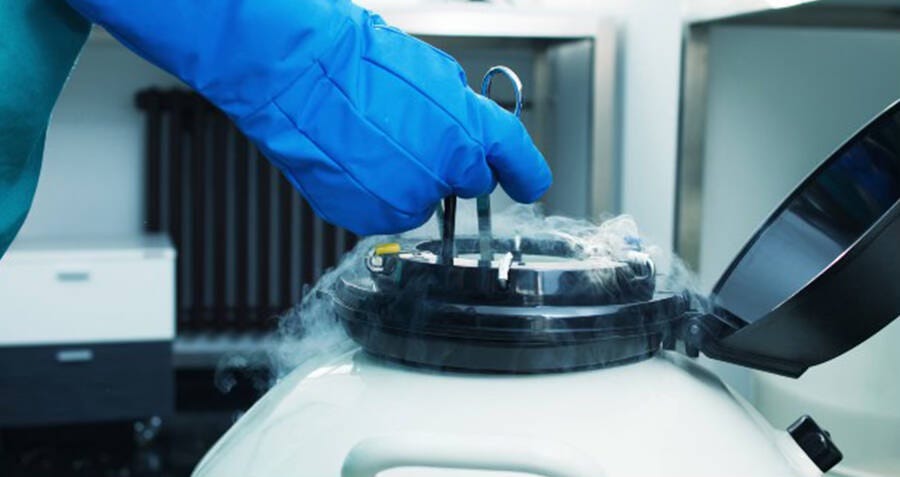

The Supreme Court of Alabama recently issued a ruling that frozen embryos are considered children under Alabama state law. Therefore, in-vitro fertilization (IVF) clinics may be liable for wrongful death claims or other damages if those embryos are accidentally destroyed. The plaintiffs in the case alleged that a patient at hospital in Mobile, Alabama, walked into the hospital's fertility clinic through an unsecured doorway and removed several frozen embryos from cryogenic storage. The meddler's hand was freeze-burned by the containers, which were kept at extremely low temperatures, and the patient dropped them on the floor, killing the embryos.

Justice Jay Mitchell, writing for the 8-to-1 majority, summarized the court's ruling:

The central question presented...which involve the death of embryos kept in a cryogenic nursery, is whether [Alabama's Wrongful Death of a Minor] Act contains an unwritten exception to that rule for extrauterine children.... The answer to that question is no: the [Act] applies to all unborn children, regardless of their location.... Unborn children are "children"...without exception based on developmental stage, physical location, or any other ancillary characteristics.

The sole dissenting justice opined, "the main opinion's holding almost certainly ends the creation of frozen embryos through [IVF] in Alabama." IVF practitioners and fertility industry lobbyists responded similarly: instead of reassurances that frozen embryos would be carefully guarded and protected from accidental destruction, some—like the University of Alabama at Birmingham health system—paused their IVF services while they assess potential liability. Critics of the ruling scoff at the notion that an embryo would be considered a child, with some dismissing the embryo as merely a "clump of cells," rather than a whole and genetically distinct human being in his or her earliest stage of development.

Most other state laws consider the embryo to be the "property" of the parents, which hardly resolves the ethical questions (human life as property is the legal definition of slavery) or the legal conundrums. Actress Sofia Vergara and Nick Loeb famously engaged in a seven-year-long legal battle over custody of their frozen embryos following their breakup in 2014. It is hard to imagine such pitched battles being waged over a mere clump of cells. Why should either disputant care what the other intends to do with such negligible biological material?

Similarly, we cannot imagine an IVF clinic doctor telling a couple, "your embryo was accidentally discarded; but not to worry, we have plenty of spare embryos you can use. One tiny clump of cells is as good as another." No sane parents would accept this, for the "spare" embryo—even if he or she is healthier—is not their child. The considerable trouble, expense, risk, and emotional toll of IVF attests to the invaluable status of the precious "product" it produces: a new human life—and not just any human life but a child of one's own.

The Alabama case highlights thorny problems with IVF that are often ignored. This is a highly profitable industry, with each IVF cycle costing on average $15,000 (plus $5,000 for medications). Multiple cycles are frequently necessary to achieve pregnancy, and even then, a baby is far from guaranteed. Clinics compete in the market based on success rates. Because egg harvesting is an invasive and sometimes risky procedure, IVF cycles typically aim to create many embryos as possible—usually more than the couple intends to bring to birth. Unused embryos go into cryo-storage but can later be thawed and implanted. In one 2022 experiment, twins were born after 30 years in cold storage; their adoptive father was five years old when they were created.

It is not known precisely how many embryos are now in cold storage, because clinics are not required to report these numbers. Estimates range from 500,000 to millions. Many of these end up abandoned by parents who stop paying the $500 to $1,000 yearly storage fees and fail to respond to repeated requests from clinics. Most parents remain reluctant to allow clinics to destroy their spare embryos, suggesting at least moral ambivalence. Other available options include adopting out their embryos to another infertile couple or donating them to embryo-destructive research. Parents likewise rarely consent to these, likely out of similar moral reticence. These parents know well what happens when those "clumps of cells" are placed in a mother's womb.

Thus, parents who do not want to raise additional children are stuck in an insoluble ethical conundrum and their embryos are left in a cryogenic nursery limbo. It's hard to entirely blame IVF clients for this situation when all available choices seem morally problematic. Even when they are informed of these options before starting IVF, most couples admit that they were singularly focused on achieving a pregnancy and rarely considered what would happen to their excess embryos until they faced the decision later.

In creating hundreds of thousands of human embryos that will never be placed in a nurturing uterus—the only conducive environment for embryonic life—we have entered a situation in which there is no morally just solution. This should invite us to reevaluate the practice that created this insoluble quandary in the first place.

Those who complain that the Alabama decision will hamper access to IVF usually fail to mention that it's always been a service geared toward well-off couples who can afford it. Furthermore, our near-singular focus on IVF as the standard work-around for infertility (note that it does not actually treat or cure infertility) has arguably hampered medical research into infertility's causes and potential treatments. We should do more to develop affordable medical interventions for infertile couples—options that will not involve the creation of "excess" embryonic human life, condemned to either exist indefinitely in a frozen state of suspended animation or be discarded with the morning's trash. A civilized society should not condone cryogenic nurseries.

This is a personal question for me. I declined doing IVF on moral grounds and used the Catholic church's Napro Technology. I have a healthy, happy 13 year old conceived naturally and no ethical/moral quandary about unused embryos. More people should know this is possible.

As always with complex and thorny ethical problems, there are many who are ready to offer simple Gordian knot solutions that strip away the complexities of the problem and lead us into oblivion. While the moral dilemmas of IVF clearly call for a thoughtful discussion, who will make it happen, who will participate in the discussion, who will assure that the discussion is fair-minded and not overly influenced by bias? When we enter the world of medical ethics, subjectivity quickly rises to the surface and is not easily corralled. It is always a risk that we enter the Socratic world where nearly any postulate inevitably brings us to a place of absurdity. Yet tackle it we must. Good article. I hope many will read it.