Supreme Court Oral Arguments: In-Depth Analysis, Part 2

My commentary on the our oral arguments and the Justices’ interrogations, with my conjectures regarding how the Court will rule on the injunction in June.

See Part 1 for my analysis and commentary of the government’s oral arguments and the Justice’s interrogations of the government.

The Solicitor General of Louisiana, who argued the case for our side, opened by pointing out that the government has many levers for coercion of social media companies, and they have been aggressively deployed since at least 2020. The platforms initially tried to push back but eventually caved under relentless government pressure to censor. He also argued that while governments have the right to attempt to persuade by making public arguments, governments have no right to “persuade” by censoring the views of others and using their power to suborn social media companies behind-the-scenes. As I explained in my previous post, any so-called “persuasion” in this context has powerful carrots and severe sticks attached—even when threats are not explicitly stated.

Returning to a theme he explored with the government’s attorney, Justice Thomas asked whether coordination could be deployed in addition to coercion in ways that might be unconstitutional. Our lawyer clarified that the government cannot induce private platforms—or third-party censorship enterprises (like the Election Integrity Partnership or the Virality Project)—to do what would be illegal for the government itself to do. I will add that the analogy of the hit man is illustrative: if I hire an assassin to kill someone, that assassin is obviously responsible for the murder, but I am not thereby absolved of criminal responsibility simply because I did not pull the trigger.

Returning to the question of whether the government could try to persuade social media companies to censor, Justice Kagan argued that the government does this all the time when they reach out to platforms to give them information. But in fact, as the record shows, when they reached out it is not to give information but to make imperious demands backed up by explicit or implicit threats. Kagan then pressed the question of standing again, asking whether the plaintiffs were among the “disinformation dozen” that were clearly censored at the bequest of the government (the answer is no). She then asked whether we were directly harmed by the government (the answer is yes).

Consuming much of the oxygen in the room, the verbose and aggressive Kagan later returned to her traceability hobby horse, claiming it would be hard to tell whether the censorship in any given case was government action vs. platform action against the plaintiffs, even advancing the outrageous claim—contradicted time and again in the evidentiary record—that “it seems hard to overbear Facebook’s will.” Tell that to Mark Zuckerberg, who publicly admitted that they censored things which otherwise would not have been removed except for government pressure. (See my discussion yesterday in Part 1 for more on this issue of traceability of harms from government to plaintiffs. To reiterate, I strongly believe the Supreme Court will find, as did both lower courts, that plaintiffs’ have standing.)

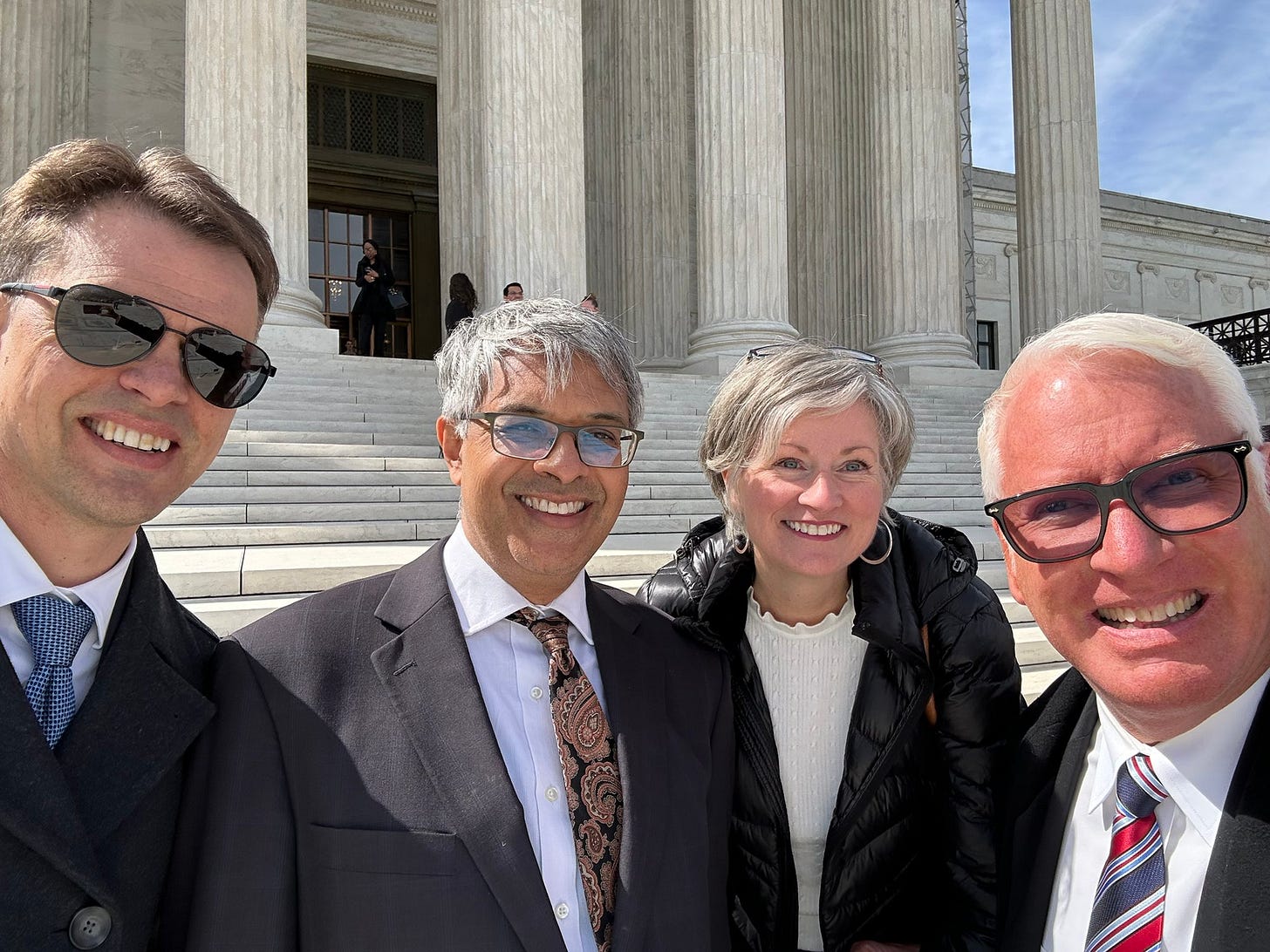

I don’t foresee Kagan getting sufficient traction on this question to overrule the two lower courts. All it would do is kick the can down the road: our attorneys round up the so-called “disinformation dozen,” add them as plaintiffs, and re-file the case. We’d be back at the Supreme Court in six months. The government only needs to find one plaintiff that has standing for the case to move forward, and two of my co-plaintiffs—Jill Hines and Jim Hoft—were specifically named in government communications to social media companies regarding censorship. I believe Kagan is pressing this point to avoid having rule on the merits: it will take some creative word-salad from Kagan, Sotomayor, and Jackson to explain how the government’s behavior was not—at the very least—coercive in many instances. Being smarter than the other two, Kagan probably wants to avoid having to twist her legal logic into a pretzel to accomplish this.

Alito and Kavanaugh, bringing the questions back to the merits and central issues at stake, raised the question again of the breadth of the injunction and its criteria for permissible vs. impermissible forms of persuasion/coercion. Gorsuch—who generally does not favor injunctions but who seems sympathetic to our arguments—cited a universal injunction in an analogous case, which, like the lower court injunction, would apply not just to the seven plaintiffs but to all those similarly situated. He asked whether the plaintiffs would accept a more narrowly tailored injunction applying only to the plaintiffs. This is obviously not our preference, but to keep Gorsuch on board our lawyer indicated that any injunction would be better than no injunction at all. We need a win—a first big dent in the censorship leviathan and a Supreme Court precedent. So we will strategically take what we can get if it means maintaining a majority of supportive justices.

Regarding coercion, Barrett asked what constitutes a threat—simply someone with authority to impose a sanction, the criteria in the Bantam Books v. Sullivan case? Our lawyer clarified that it is not only the authority to impose a threat, but even just the recipient’s belief that the authority has this power, which counts as coercion. One knows that the boxer’s hands are deadly weapons even if he does not raise his fists in a threatening pose.

Finally, I cannot fail to mention Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson’s attempt to create out of thin air a novel free speech doctrine which would permit broad latitude for government censorship and eviscerate the plain meaning of the First Amendment.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Human Flourishing to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.