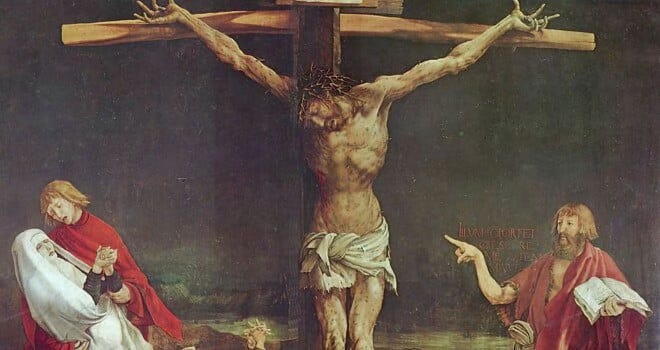

Meditating on the Passion

The latest in my Friday series during Lent on the Christian meaning of suffering and the Cross.

I’m publishing a weekly series of reflections at Catholic Exchange during Lent. Here is a brief excerpt from today’s installment, along with a link to the full article:

There are countless ways to meditate upon the suffering of Christ, and each of us can discover our own path. The point is that our meditation should be personal, for Jesus died for each one of us alone and individually, not just for an abstract mass of humanity collectively. He assumed and experienced the consequences of each one of our personal sins, and not just symbolically but experientially.

As we meditate upon and consider the Passion in relation to our own lives, the moments that stand out may not necessarily involve the “big” details, like the lashes from the scourging, but Jesus’ more insignificant wounds. Perhaps those on His face pain us the most. The abrasion on His upper left cheek that had scabbed and dried so that it could not be fully cleaned when His body was prepared for burial. The specks of dried blood on His nose that could also not be removed, because doing so would have ripped off the thin top layer of skin. The blood that matted and hardened into His beard. The taste of blood, mixed with gritty dirt, that was His only nourishment as He carried His Cross. The film of tears that crusted over His eyes and burned His skin. The torn skin across the knuckles on His fingers and hands from every time He fell while dragging His Cross. Carrying the Cross on His right shoulder would have also produced a terrible wound on His lower back over the curved top of pelvis bone, where the weight of the Cross rubbed and tore into His flesh. Perhaps that particular wound—one that we had never considered—hurt more than all of the others.

I’ll mention by way of example just one approach to meditation that has worked for me personally as a physician. I consider in prayer the wounds and suffering Our Lord endured beginning with the agony in the garden up until the moment right before the nails are driven into His hands and feet. I then imagine what I would do, as a medical doctor who cares for afflictions of the body and soul, if Jesus was brought to me as a patient in that battered state, having endured what He did. I consider everything that I would need to do to care for His physical wounds and try to heal them—from His cracked lips to His abraded knees; from the large splinters in His hands, shoulder, and back from carrying the Cross, to the bleeding lacerations from the scourging and the puncture wounds from the crown of thorns. How would I tend to each of these wounds?

I imagine needing to attend not just to His physical wounds but His emotional state as well—something I have more training and experience with since I specialize in psychiatry—but how does one counsel the Son of God? How would I support Him with my words—he who was abandoned by virtually all His friends and disciples, subjected to the worst injustices, maligned and scorned? And then I recall that all of that happened to Christ even before He bore my sins in His body on the Cross, before He was nailed to the Cross and died just for me.

As I said, this meditation might be suitable for a physician or counselor, but it may not work for others, which is fine. The point of this example is that each of us can find something like this—something suitable for our temperament and our gifts—that allows us to draw very close to Our Lord in His suffering. It should be tangible, physical, and intimate: we can touch and tend to His wounds; we can kiss His face; we can hold His hand; we can be present to Him, and He to us, in His humanity, in His bodily presence. We can try to engage all our senses and imagination to enter into His Passion, as we pray, doce me passionem Tuam—teach me your suffering.

Click here to read the rest of the article. Previous articles of the series can be read here.

Thanks and Blessings Dr. Kheriaty

Thank you for this beautifully written meditation.